Optimizing a GEMM from first principles

Table of Contents

This is a worklog on optimizing a single-precision generalized matrix-multiply (GEMM) kernel in C to land close to Intel MKL performance. In the process of learning this for myself, I found the following sources really helpful. Building on the following, this article aims to approach the design decisions of GEMM at the level of a chip ISA.

- Algorithmica: Matrix Multiplication

- Advanced Matrix Multiplication on Multi-Core Processors

- George Hotz | Programming | can you multiply a matrix? (noob lesson)

Introduction #

Let us start by describing the pointwise operation:

1void gemm_naive(float *C,

2 const float *A,

3 const float *B,

4 int M,

5 int N,

6 int K) {

7

8 for (int i = 0; i < M; i++) {

9 for (int j = 0; j < N; j++) {

10 for (int k = 0; k < K; k++) {

11 C[i * N + j] += A[i * K + k] * B[k * N + j];

12 }

13 }

14 }

15}

It takes ~1.2 seconds for this kernel to multiply two 1000-size square matrices. This is absurdly slow for a CPU of this day and age. The Intel-MKL library, in comparison, finishes this operation in 13ms, about 100x faster. Before we start optimizing this naive kernel, lets take stock of how to reason about the performance of a kernel.

Roofline Analysis #

System specs:

- Intel Xeon [Sapphire Rapids] 8488C @ 2.5GHz, 2 vCPUs

- Cache L1d: 48 KB/core | L2: 2 MB/core | L3: 105 MB/shared

- ISA support: AVX-2 | AVX-512

- Microarchitecture: Golden Cove1

- 4GB Memory, 10GB/s STREAM bandwidth (measured using

mbw) - Ubuntu 24.04 LTS

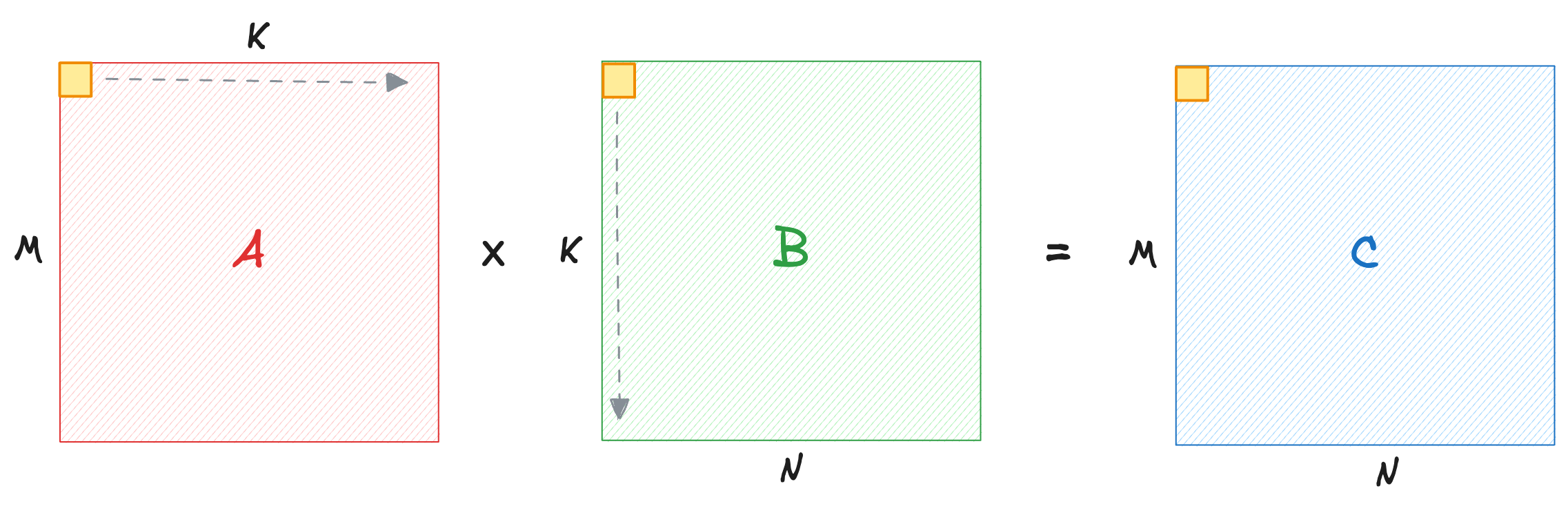

We will measure the performance of Generalized Matrix Multiply (GEMM) kernels in GFLOP/s (giga floating point operations per second). How many operations? GEMM involves K dot products across each row and column of A and B respectively to furnish each element of result matrix C.

$$ A^{M \times K} \times B^{K \times N} = 2 \cdot M \cdot N \cdot (K - 1) \approx 2 \cdot MNK $$

We apply a scaling factor of 2 because we count multiply and adds as two separate ops. For equal matrix dimensions, this is roughly \(2N^3\) FLOPs. Assuming single precision floats, each input matrix A, B of size \(4 \cdot N^2\) bytes will be read once. Output matrix of size \(4 \cdot N^2\) bytes will be read and written back to memory. Therefore any kernel will read/write at least \(4 \cdot (4 \cdot N^2) \) bytes.

It is clear that total math ops grow faster than total memory read/writes. This ratio of floating point ops per byte of data moved is called the arithmetic intensity of an operation. For GEMM, arithmetic intensity \(\alpha\) is:

$$ \alpha = \frac{\text{ \char"0023 operations }}{\text{ \char"0023 bytes transferred }} = \frac{2N^3}{16N^2} = \frac{N}{8} \text{ FLOPs/byte } $$

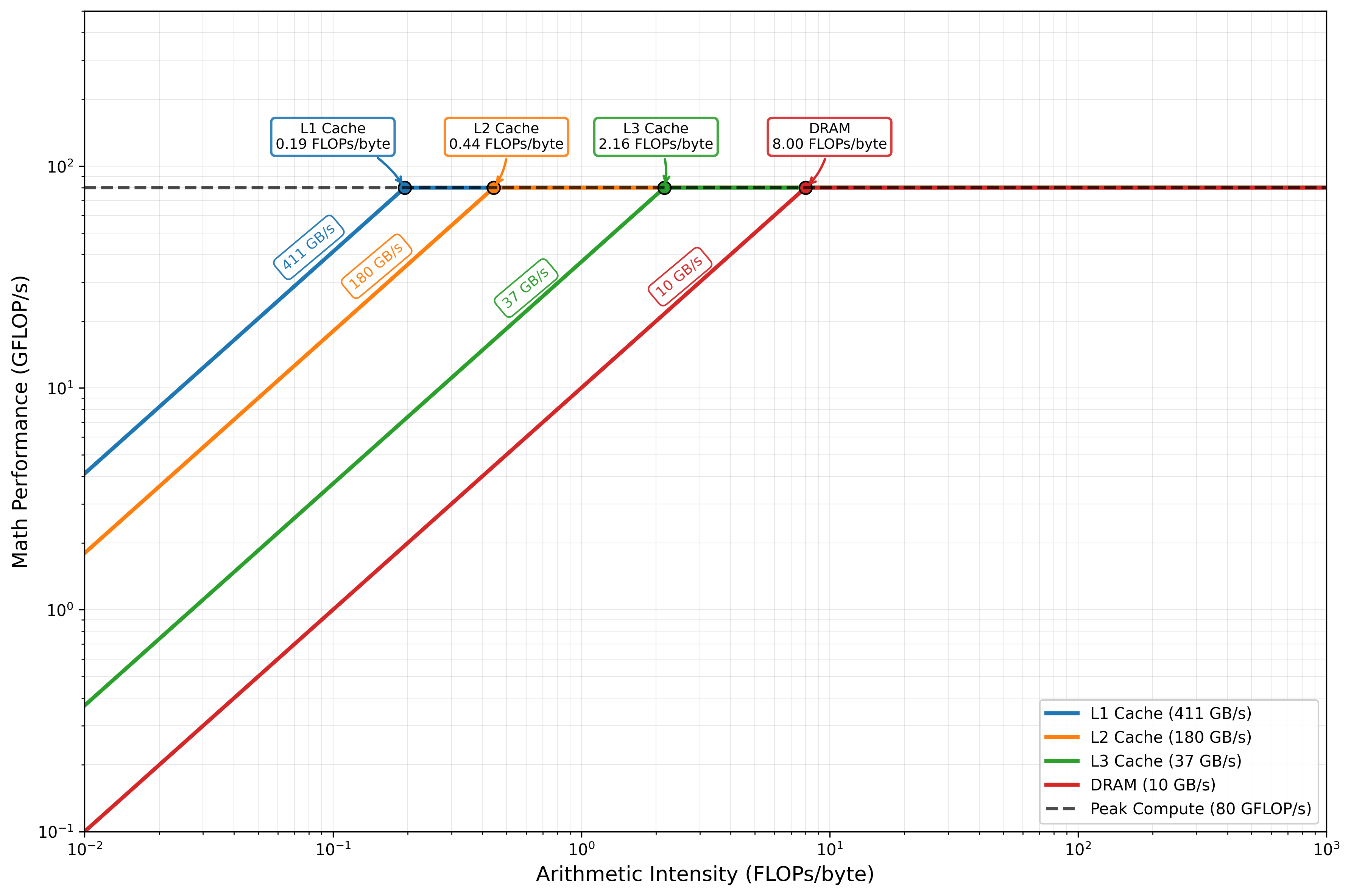

This means that as matrix sizes grow, GEMM operation becomes compute-bound. In fact, if we know the compute and memory bandwidth of a machine, we can find the machine’s ‘ridge point’. Any kernel that uses less FLOPs/byte from the ridge point is said to be memory-bound, and vice versa.

Intel Golden Cove core has two FMA (fused multiply-add) units that can operate on 256-bit width vectors simultaneously. In single precision, this means 8 floats per vector. Each core also has 16 registers that are accessible in a single clock cycle. Registers sit on top of the memory hierarchy. FMA units have a latency of 4 clock cycles, and a throughput of 2 IPC2. GEMM being an arithmetic demanding operation, we care only about FMA streaming throughput. The first-dispatch latency therefore is not relevant. This gives us enough information to calculate the compute bandwidth:

$$ 2 \text{ ops } \times 2 \text{ IPC } \times 8 \text{ floats/cycle } \times 2.5 \text{ GHz } = 80 \text{ GFLOP/s } $$

The DRAM bandwidth on our setup is 10GB/s per thread from a simple mbw benchmark. Therefore, the ridge point \(\gamma\) of this CPU across DRAM is:

$$ \gamma = \frac{\text{compute BW}}{\text{memory BW}} = 8 \text{ FLOPs/byte } $$

In practice, the ridge point depends on cache reuse, branching, and other instruction overheads. For instance, if we manage to keep the entire working set of a GEMM operation within cache boundary (which we will see soon with a cache-blocked GEMM kernel), the arithmetic intensity necessary to saturate compute units is quite lower. Here is a roofline model of the entire memory hierarchy and the corresponding ridge points. The focus of this worklog is on single-threaded operations only.

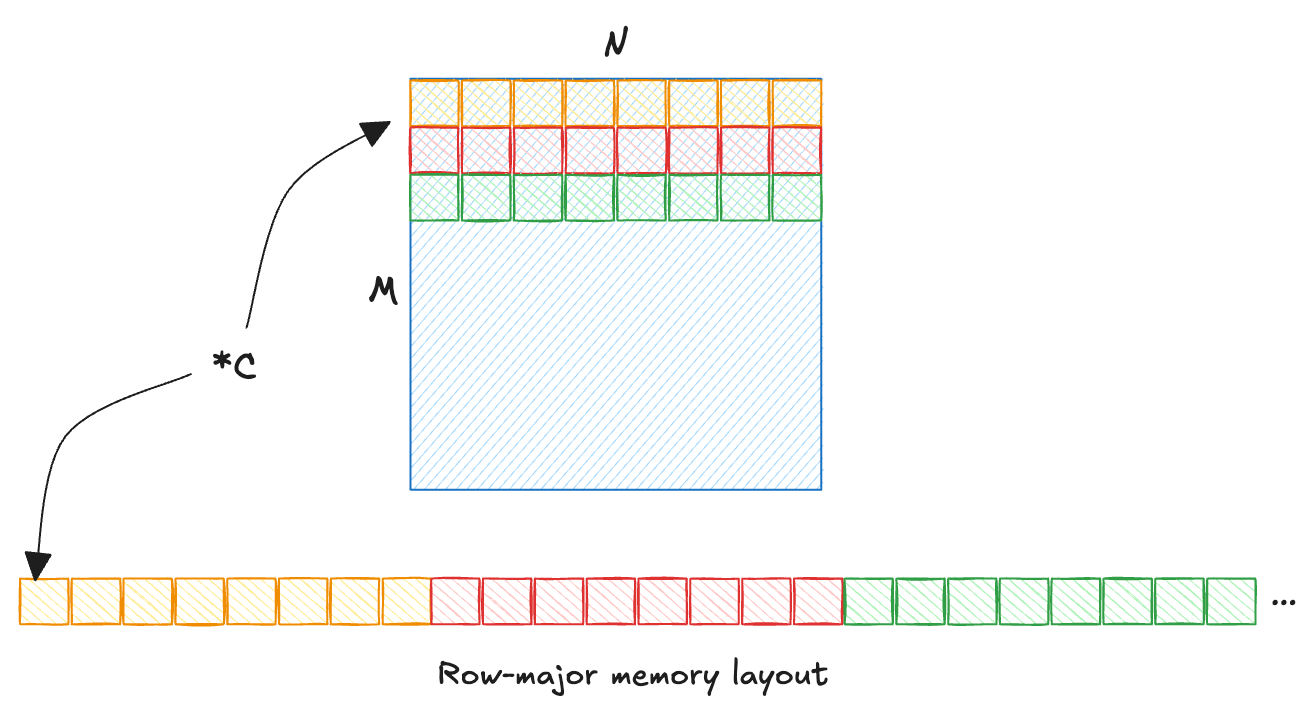

Memory Layout #

As mentioned earlier, our arrays store floats in a row-major order, i.e., elements of a row are laid out consecutively. CPUs fetch contiguous blocks of memory (called a cache line) in the hope that consecutive memory elements will be needed for further processing. If a computation does not utilize all items in a cache line optimally, CPU cycles are wasted.

This gives us a couple of observations:

- Innermost loop iterates the fastest, over dimension

K. - Array

A[M * K]hasKcolumns, with each elementA[i][k]consecutively laid out in memory. Therefore, iteration overKis cache-friendly. - Array

B[K * N]hasKrows, each elementB[k][j]requires jumping an entire row ofNelements in memory. This results in a poor cache utilization. - Array

C[M * N]hasjas the fastest moving dimension, i.e., the second loop. It is consecutively laid out in memory, and is cache-friendly.

Spatial Locality #

Iterating over rows of B is the problem. Notice that the nested for-loops are order-independent, and array C does not depend on dimension K. Therefore, we can reorder the loops such that iterating over K dimension is slower, and hence less costly for B.

1/** Basic loop-reordered, pointwise GEMM kernel. */

2void gemm_loop_reorder(float* __restrict C,

3 const float* __restrict A,

4 const float* __restrict B,

5 int M,

6 int N,

7 int K) {

8

9 for (int i = 0; i < M; i++) {

10 for (int k = 0; k < K; k++) {

11 for (int j = 0; j < N; j++) {

12 C[i * N + j] += A[i * K + k] * B[k * N + j];

13 }

14 }

15 }

16}

By swapping j <-> k, we retain cache-friendliness of A and C, while reusing the element B[k][j] for N iterations before incurring a cache miss. We still incur the same number of misses. We are simply amortizing the cost of each cache-miss by reusing the fetched element as long as possible.

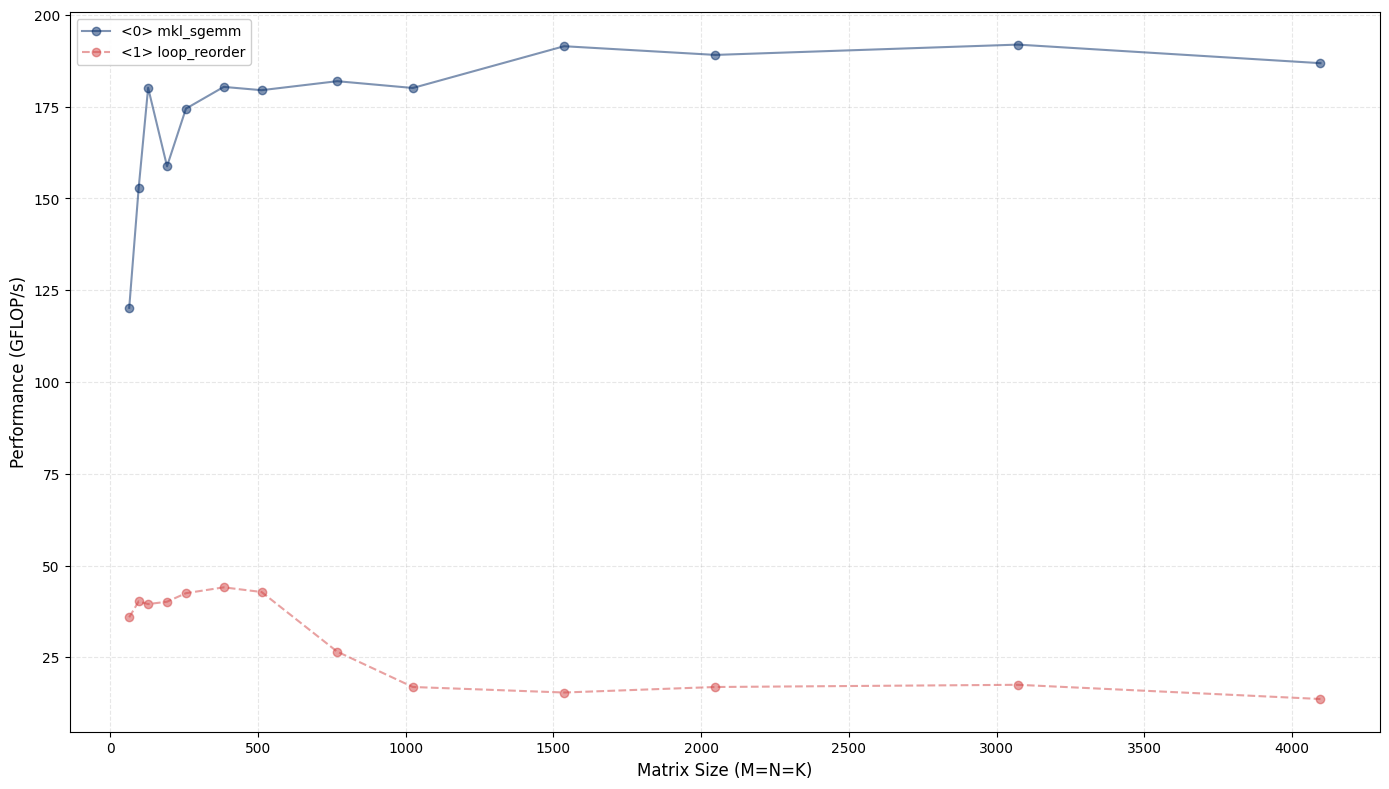

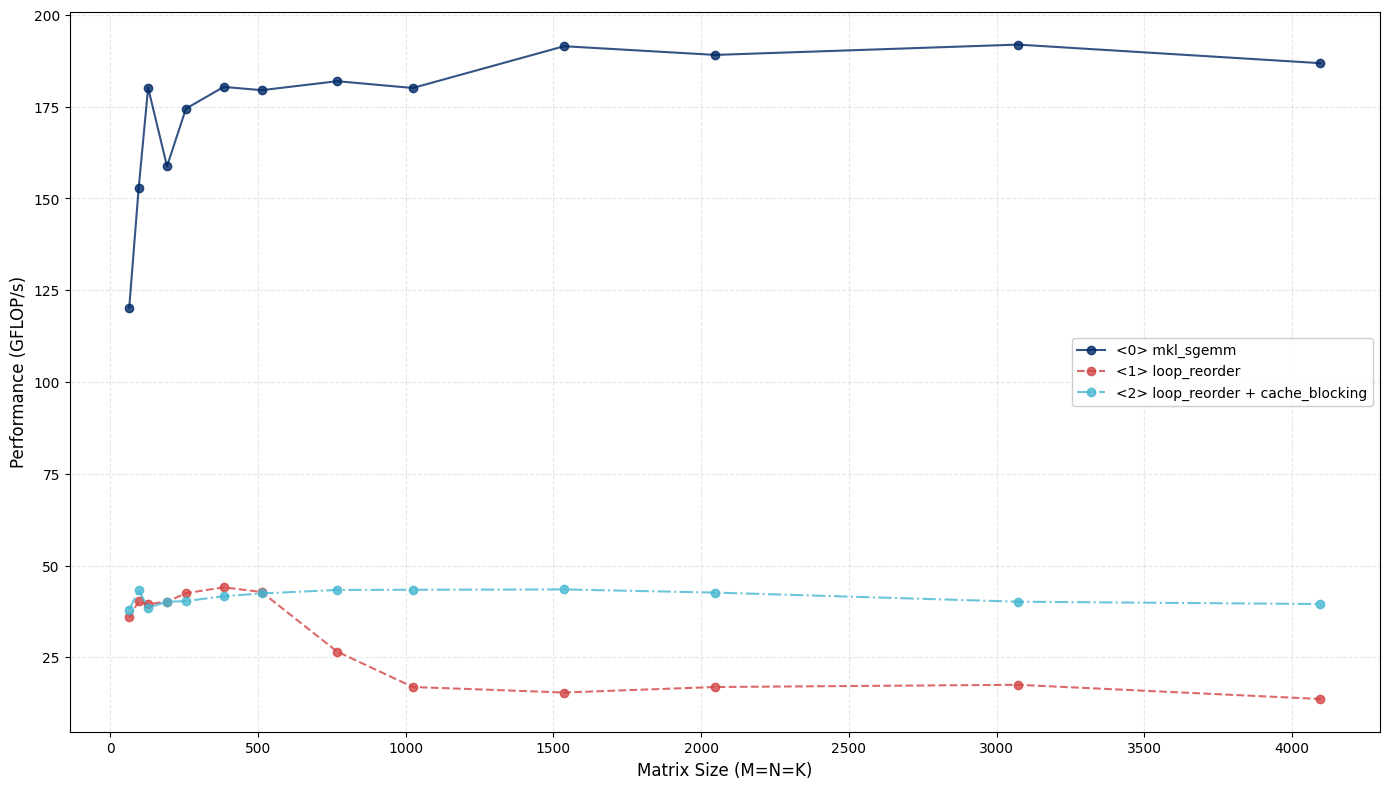

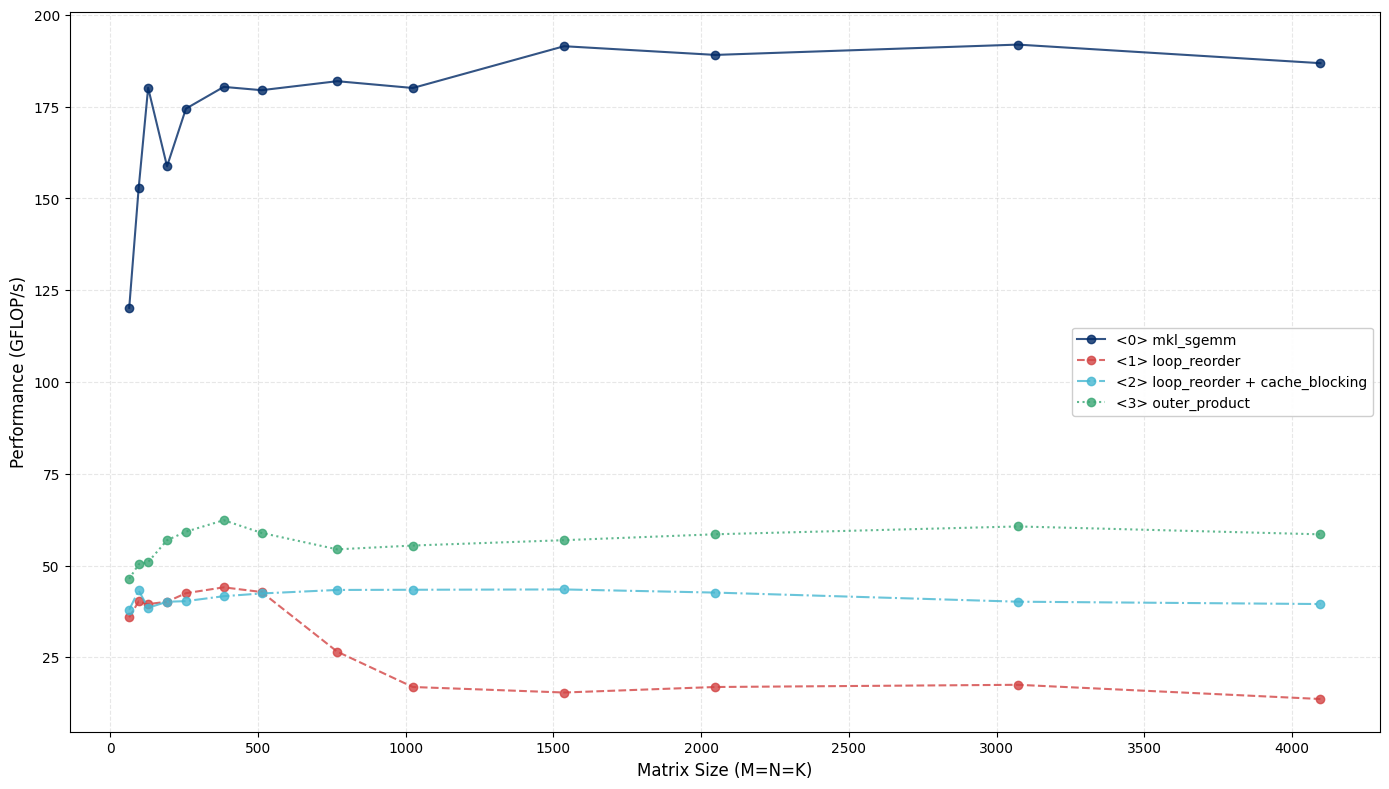

On small matrices, this simple tweak boosts our GFLOP/s by 10-25x, saturating on the lower end as matrices grow large. What explains this jump? Can performance be sustained over large matrices?

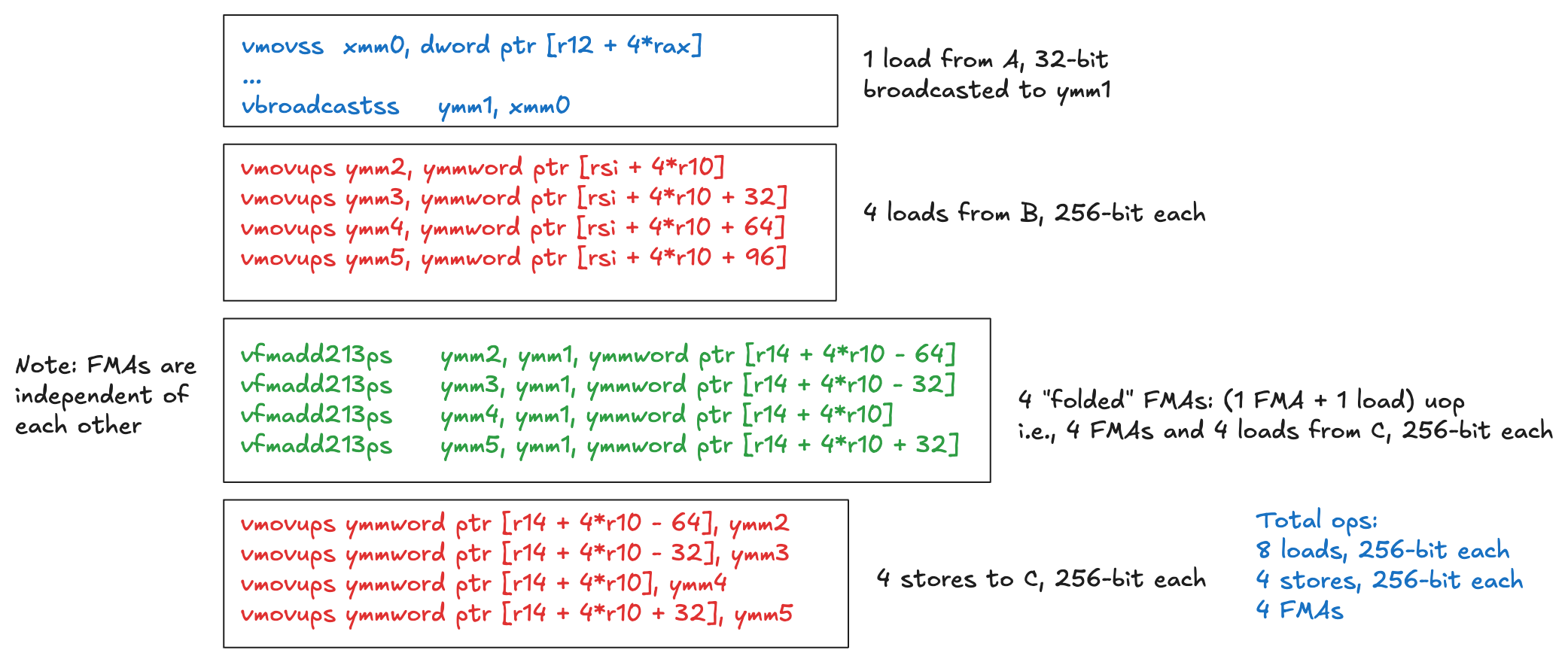

Implicit Vectorization #

Even though our loop-reordered kernel defines scalar operations, improved spatial locality on B allows the compiler (with -O2 flag) to fuse scalar operations into vector FMA instructions. We can see this in the disassembly of the kernel.

.LBB0_19:

vmovups ymm2, ymmword ptr [rsi + 4*r10]

vmovups ymm3, ymmword ptr [rsi + 4*r10 + 32]

vmovups ymm4, ymmword ptr [rsi + 4*r10 + 64]

vmovups ymm5, ymmword ptr [rsi + 4*r10 + 96]

vfmadd213ps ymm2, ymm1, ymmword ptr [r14 + 4*r10 - 64]

vfmadd213ps ymm3, ymm1, ymmword ptr [r14 + 4*r10 - 32]

vfmadd213ps ymm4, ymm1, ymmword ptr [r14 + 4*r10]

vfmadd213ps ymm5, ymm1, ymmword ptr [r14 + 4*r10 + 32]

vmovups ymmword ptr [r14 + 4*r10 - 64], ymm2

vmovups ymmword ptr [r14 + 4*r10 - 32], ymm3

vmovups ymmword ptr [r14 + 4*r10], ymm4

vmovups ymmword ptr [r14 + 4*r10 + 32], ymm5

This core has vector registers for single-precision floats: 16 ymm registers, each holding 8 floats. (Other instruction sets like SSE and AVX-512 use different register widths, but we focus on ymm here.) These registers sit at the top of the memory hierarchy and are the fastest to access.

When using ymm registers with 256-bit vectors, the performance ceiling is limited by the load/store capacity, as we’ll analyze in detail. On small matrices, this loop-reordered kernel is an order of magnitude faster because the active blocks fit within the L2 cache boundary. As the matrix size grows, performance plateaus until active blocks fit L3. For even larger matrices, the active blocks exceed cache boundary, and require multiple read/writes into the main memory.

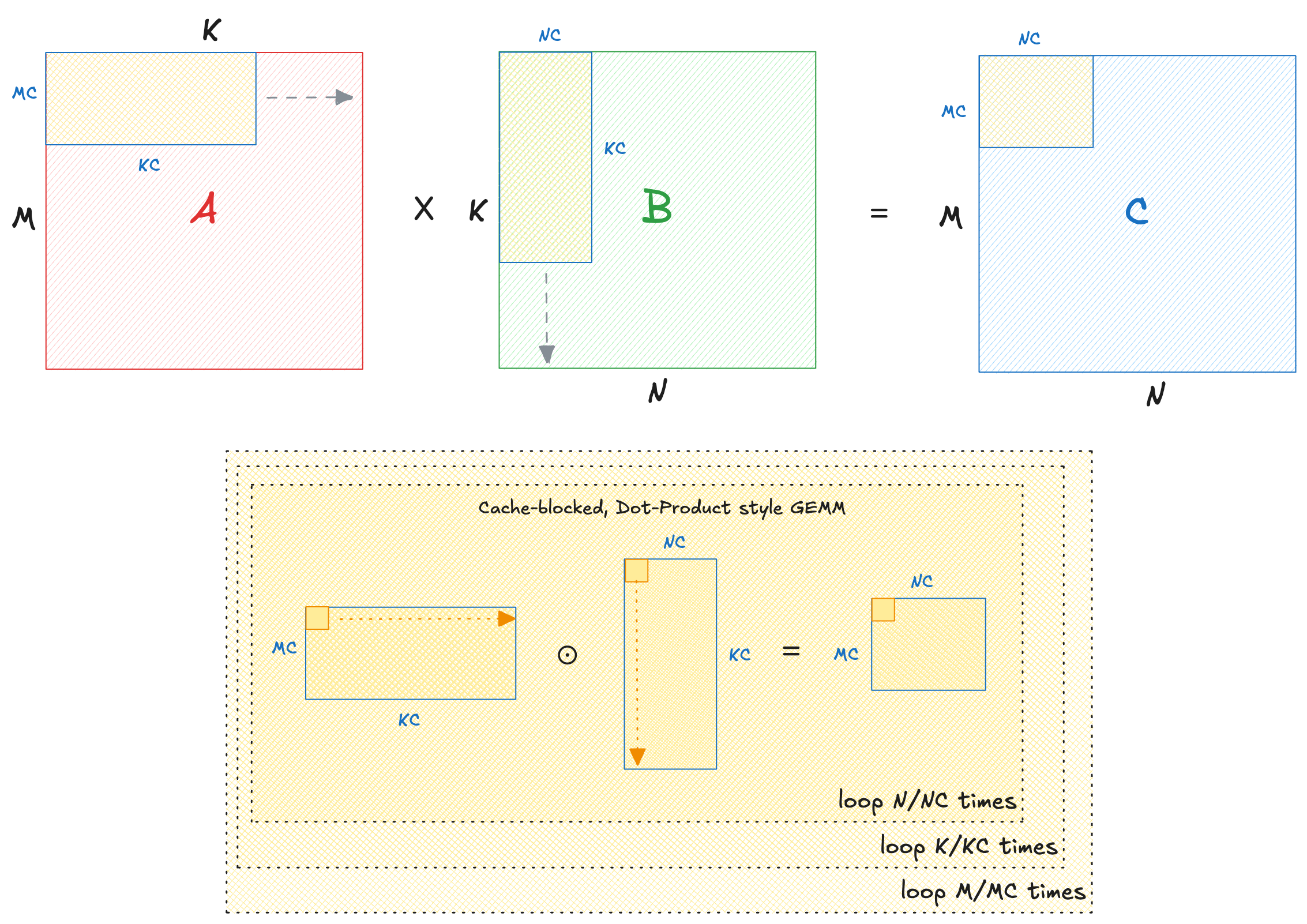

Cache blocking #

Cache size is limited. As matrix dimensions grow, there is a possibility of older cache lines being ’evicted’ to fetch elements for the next iteration. This leads to wasteful load/stores and lower arithmetic intensity for large matrix sizes. We solve this by slicing each of the three dimensions into ’tiles’, and executing smaller, cache-friendly matrix multiplies on those tiles. Tuned how?

1/** Cache-blocking across dimensions. */

2#define TILE_K 128

3#define TILE_N 2048

4#define TILE_M 1024

5

6void gemm_cache_blocking(float* __restrict C,

7 const float* __restrict A,

8 const float* __restrict B,

9 int M,

10 int N,

11 int K) {

12

13 // Tile across each dimension

14 for (int i = 0; i < M; i += TILE_M) {

15 const int mc = min(TILE_M, M - i);

16 for (int k = 0; k < K; k += TILE_K) {

17 const int kc = min(TILE_K, K - k);

18 for (int j = 0; j < N; j += TILE_N) {

19 const int nc = min(TILE_N, N - j);

20

21 // Update partials on each tile

22 for (int ir = 0; ir < mc; ir++) {

23 for (int p = 0; p < kc; p++) {

24 for (int jc = 0; jc < nc; jc++) {

25 C[(i + ir) * N + (j + jc)] +=

26 A[(i + ir) * K + (k + p)] * B[(k + p) * N + (j + jc)];

27 }

28 }

29 }

30 }

31 }

32 }

33}

With cache-blocking, performance is consistent across all matrix sizes. The disassembly of this kernel is same as before. This is expected because the same instructions now run on ’tiles’ of matrices.

Performance ceiling #

So our kernel uses 256-bit FMAs, and cache-blocking to sustain GFLOP/s. Recall from our roofline analysis, the performance ceiling is 80 GFLOP/s. To understand the reason behind saturation at 40 GFLOP/s, review the disassembly:

From the Golden Cove microarchitecture, we find the following uOp capacities:

| Op | Capacity (per cycle) | Requirement | Cycles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loads | \(3 \times 256\) | \(8 \times 256\) | \(2.67\) |

| Stores | \(2 \times 256\) | \(4 \times 256\) | \(2\) |

| FMAs | \(2\) | \(4\) | \(2\) |

A is broadcasted to ymm1 and reused for the entire iteration. The load cost is negligible compared to the rest, hence ignored in calculations.Loads take approximately 2.67 cycles. FMAs execute as soon as the operands are ready, and hence the load ops ‘mask’ the 2 cycles consumed by FMAs. Stores take 2 cycles after FMAs retire. So the percentage of ‘useful’ multiply-add work:

$$ \frac{2 \text{ FMA}}{2.67 \text{ loads } + 2 \text{ stores}} = \frac{2}{4.67} \approx 0.43 $$

Our performance ceiling with this kernel is \(0.43 \times 80 = 34.4 \text{ GFLOP/s}\). This matches the GFLOP/s we see in practice.

Outer Product #

So far we have been looking at matrix multiplication as repeated dot products between rows of A and columns of B:

$$

C_{ij} = \sum_{k=1}^K A_{ik} \cdot B_{kj}

$$

Dot products are inefficient on hardware for the following reasons:

- Frequent Load/Stores for

C: Tiles ofCare read and written repeatedly. This is clear from our disassembly analysis. The useful FMA work is capped at 43%. - Poor Register Utilization: Registers are the fastest to access in the memory hierarchy. Vector intrinsics on modern cores like Golden Cove have 16 vector registers (32 in AVX-512). The dot-product loop uses about 6-7 registers for temporary accumulations.

- Arithmetic Intensity: GEMM gets more compute intense with size. Our current implementation is load/store bound at large sizes. We need to amortize the cost of load/stores with more arithmetic work.

Matrix-multiply as an outer product #

Matrix multiply can be rewritten as a cumuluative outer-product between columns of A and rows of B:

$$

C = A \times B = \sum_{k=0}^{K-1} A_{:,k} \otimes B_{k,:}

$$

Here is an example of a vector outer product with \(a^{2 \times 1} \otimes b^{1 \times 2}\): $$ a \otimes b = \begin{bmatrix} a_0 \\ a_1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} b_0 & b_1 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} a_0 b_0 & a_0 b_1 \\ a_1 b_0 & a_1 b_1 \\ \end{bmatrix} $$

In the notation:

- \(A_{:,k}\) is the \(k\)-th column of

A(an \(M \times 1\) vector). - \(B_{k,:}\) is the \(k\)-th row of

B(a \(1 \times N\) vector).

Their outer product (\(\otimes\)) produces an \(M \times N\) matrix where each element is \(A_{i,k} \cdot B_{k,j}\). Summing these over all \(k\) gives the full \(C\).

This is algebraically identical to the dot-product view but shifts the focus: instead of accumulating inward along \(k\) for each fixed \((i,j)\), we are broadcasting outward from each \(k\), adding a full “layer” to \(C\) at a time.

What motivates this reformulation?

- Register Reuse: In the outer-product view, we can load slices of \(A_{:,k}\) and \(B_{k,:}\) into registers, compute their outer product, and accumulate it directly into a register-resident tile of \(C\). Registers are plentiful (16 YMMs can hold 128 floats total), so we can “block” a small \(\text{MR} \times \text{NR}\) tile of \(C\) using multiple ZMMs.

- Load/Store Amortization: After several updates over \(k\), we store the \(\text{MR} \times \text{NR}\) tile of \(C\) back to memory. This amortizes load/store costs over more FMAs.

- Higher Arithmetic Intensity: By accumulating multiple outer products in registers, the ratio of computations to memory accesses increases.

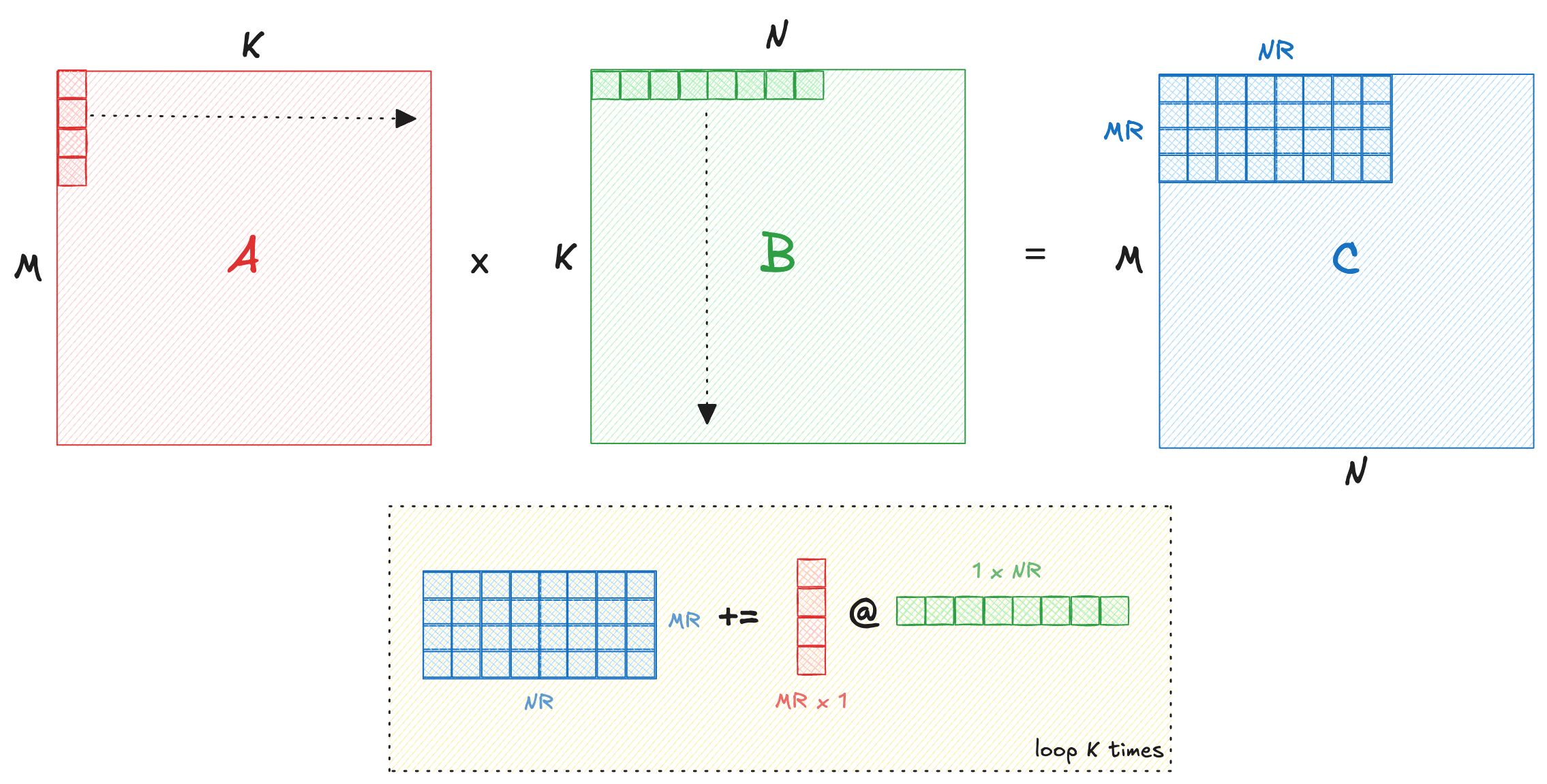

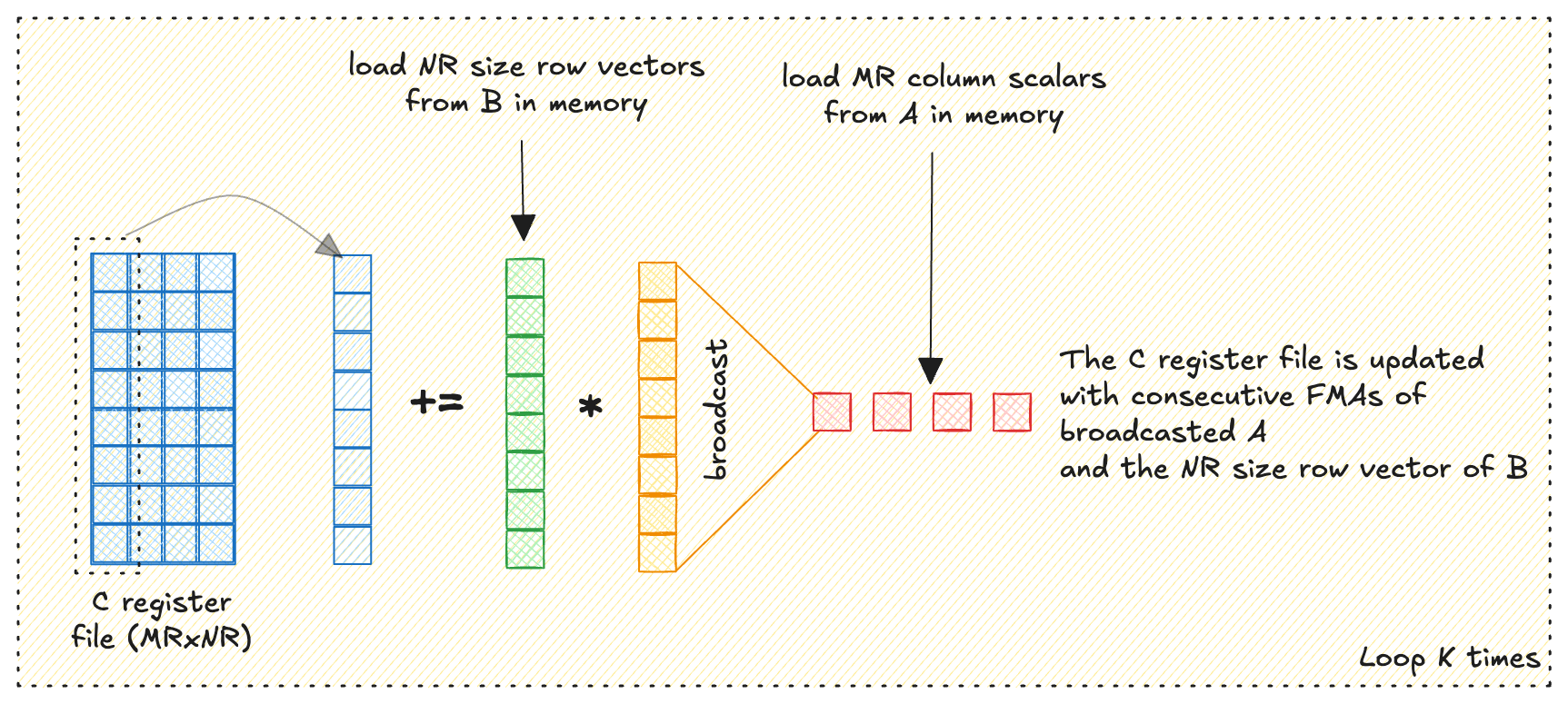

Outer Product using Registers #

CPUs do not have an intrinsic for vector outer product, which means we need to compute one iteratively using vector FMAs.

Consider loading \(\text{MR}\) scalars from \(A\) across the column, and \(\text{NR}\) scalars from \(B\) across the row.

A into a buffer, which gets passed into the outer-product microkernel. Transposed A is cache-friendly and reuses the same for K outer products. Check code for details.We iteratively broadcast + FMA each of the scalars from \(A\) to vectors of \(B\), cumulatively storing the result in an \(\text{MR} \times \text{NR}\) register tile of \(C\).

Here is a pseudocode of the inner loop:

fn micro_gemm(...):

<!-- m=MR scalars of A -->

<!-- n=NR/8 vectors of B -->

a = {}

b[NR/8] = {}

c[MR][NR/8] = {}

<!-- Load tile from C -->

for m in MR:

for n in NR/8:

c[m][n] = load(C[m][n])

<!-- Loop over inner dimension -->

for p in K:

b[1], ..., b[NR/8] = load(B[:NR])

<!-- One iteration (hot FMA loop) -->

for m in MR:

a = broadcast(load(A[m]))

<!-- Outer product within registers -->

for n in NR/8:

c[m][n] = fma(a, b[n], c[m][n])

A += MR

B += NR

<!-- Store back to C -->

for m in MR:

for n in NR/8:

store(c[m][n], C[m][n])

Optimal Tile Size #

When using YMM vector registers, we have a limit of 16. The scalars we load from \(B\) of size \(\text{NR}\) must be a multiple of 8 to fit in one register. Hence \(B\) vector will use \(\text{NR}/8\) registers. Each scalar from \(A\) uses 1 register: the scalar is broadcasted to the entire vector. The \(C\) accumulator fully resides in registers, requiring \(\text{MR} \times \text{NR}/8\) registers. Therefore, we need to satisfy the inequality:

$$ \text{MR} \cdot \frac{\text{NR}}{8} + \frac{\text{NR}}{8} + 1 \leq 16 $$

Since \(\text{MR} \ge 1\) and \(\text{NR} \ge 8\) is necessary, we have the following acceptable combinations:

$$ \begin{array}{|c|c|c|c|c|c|} \hline \text{MR} & \text{NR} & \text{YMM register ct.} & \text{Loads/iter (bytes)} & \text{FLOPs/iter} & \text{FLOPs/byte} \\ \hline 1 & 56 & 15 & 228 & 112 & 0.491 \\ 2 & 40 & 16 & 168 & 160 & 0.952 \\ 4 & 24 & 16 & 112 & 192 & 1.714 \\ 6 & 16 & 15 & 88 & 192 & 2.182 \\ 14 & 8 & 16 & 88 & 224 & 2.545 \\ \hline \end{array} $$

Only the \(6 \times 16\) and \(14 \times 8\) size micro-kernels are capable of saturating the core within L3 boundary (recall from the roofline plot, \(2.16 \text{ FLOPs/byte}\)), so we can discard other candidates. Of the two that remain, \(14 \times 8\) tile actually ends up being load bound. The disassembly shows a memory broadcast on every FMA; compilers tend to generate memory-source FMAs instead of separating the load and broadcast into registers. As a result, even though the total number of bytes accessed is similar, each scalar requires its own load op during the FMA. This leads to roughly 15 load instructions per iteration (14 scalar loads plus one 256-bit vector load).

By contrast, the \(6 \times 16\) micro-kernel performs six scalar loads and two 256-bit vector loads, for a total of eight loads. This produces a much better balance between load throughput and FMA issue rate, allowing the kernel to approach core saturation. This explains the popular choice of \(6 \times 16\) in various BLAS libraries using AVX intrinsics.

Cache Blocking (again) #

We tile across of the three dimensions of the matrices and sequentially compute GEMM on each one of them. This brings us within ~50% range of Intel-MKL. Note that because we use half of the full 512-bit vector instructions, this is close to the hardware limit at the given width!

1#define MR 6

2#define NR 16

3

4#define KC NR * 256

5#define NC 128

6#define MC MR * 256

7

8void gemm_outer_product_cache_blocking(float * __restrict C,

9 const float * __restrict A,

10 const float * __restrict B,

11 int M,

12 int N,

13 int K) {

14 for (int i = 0; i < M; i += MC) {

15 const int mc = min(MC, M - i);

16 for (int p = 0; p < K; p += KC) {

17 const int kc = min(KC, K - p);

18 pack_tileA(blockA, &A[i * K + p], mc, kc, K);

19 for (int j = 0; j < N; j += NC) {

20 const int nc = min(NC, N - j);

21 pack_tileB(blockB, &B[p * N + j], nc, kc, N);

22

23 // Update each tile.

24 for (int ir = 0; ir < mc; ir += MR) {

25 for (int jr = 0; jr < nc; jr += NR) {

26 const int mr = min(MR, mc - ir);

27 const int nr = min(NR, nc - jr);

28 micro_gemm(&C[(i + ir) * N + (j + jr)],

29 &blockA[ir * kc],

30 &blockB[jr * kc],

31 mr, nr, kc, N);

32 }

33 }

34 }

35 }

36 }

37}

Wider Registers #

We now have a playbook. We rewrite the same kernel with 512-bit intrinsics, and compute ideal values of MR and NR that saturate the FLOPs/byte. In my case, MR=8, NR=48 comes within 95% of Intel MKL.